Evolutionary games and information theory

Contents

In this post, I’d like to elucidate a particularly interesting relationship between two seemingly unrelated fields. This post draws a lot from a paper by John Baez and Blake Pollard [1].

Introduction to information theory

Lately, I’ve been doing some reading [2] on evolutionary games, while simultaneously taking a course in information theory. To my surprise, there appears to be some overlap between the two fields in the context of ecology and evolutionary biology. This section will explain a few of the most important concepts from information theory before getting into the main topic.

Shannon entropy

Information theory is all about how certainty can facilitate the acquisition of information. Perhaps the most important idea in information theory is the idea of entropy, which was ingeniously defined by Claude Shannon in the 1940’s for a probability mass function $p(x)$ on a sample space $X$ as:

\[H(X) = -\sum_{x \in X}log_{2}(x) p(x)\]There’s also a definition for continuous distributions, but we needn’t worry about that. Now, why is the logarithm base 2? Well, it actually doesn’t need to be, but Claude Shannon decided that this would be the best definition for computing the entropy of a message sent using a binary alphabet (which was the motivation behind information theory). We measure entropy in units of ‘bits’ under the $\log_2$ definition.

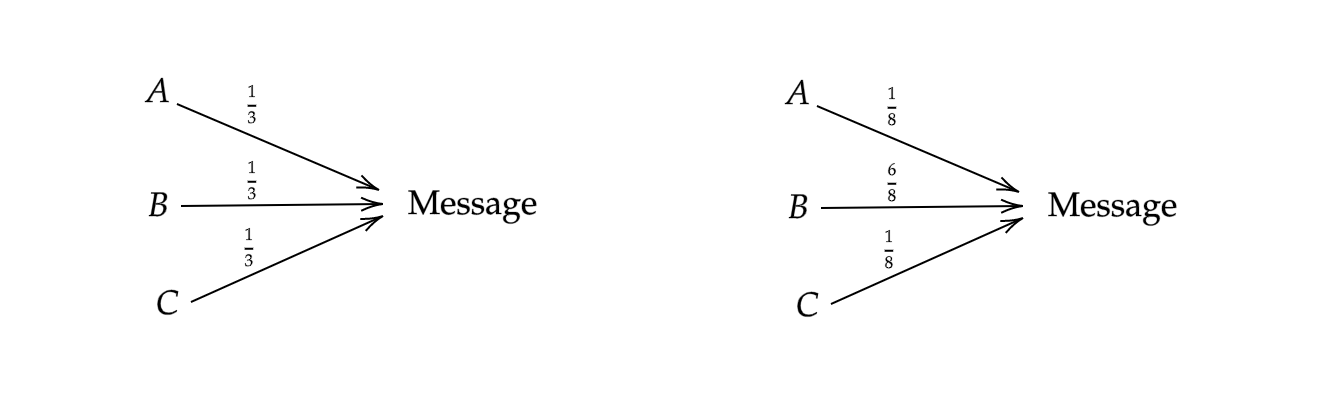

To really appreciate the beauty of this definition, consider the following example. Suppose we are receiving a message that is read in an alphabet of three letters ${A,B,C}$. Now suppose that for sending messages translated from two different spoken languages, the frequency that we receive the letters follow either of two distributions, $p$ or $q$. Define $p$ uniformly such that $p(x)=\frac{1}{3}$ for all $x$, and $q(x)$ such that $q(A) = q(C) = 1/8$ and $q(B)= \frac{6}{8}$ (See Figure 1):

Let’s compute the entropy of the signal in both languages. For the uniform signal:

\[H(p) = 3 \cdot -\frac{1}{3} \log_2(\frac{1}{3}) \approx 1.58\]For the other signal:

\[H(q) = -2 \cdot \frac{1}{8} \log_2(\frac{1}{8}) - \frac{6}{8}\log_2(\frac{6}{8}) \approx 1.06\]Clearly, the nonuniform distribution is lower in entropy. We should expect this, since it is more likely to receive the letter $B$ in the second distribution. For the first distribution, we are extremely uncertain as to what letter we will receive. Thus, as advertised, Shannon’s entropy function is measuring the uncertainty in a random variable’s outcomes.

Relative entropy

Now, let’s look at an equally important definition, known as relative entropy, which is defined for two distributions $p(x)$ and $q(x)$:

\[D(p||q) = \sum_{x\in X} p(x) \log_2(\frac{p(x)}{q(x)})\]Let’s see how this definition works by applying it to the previous example. The relative entropy of $X_1$ and $X_2$ is:

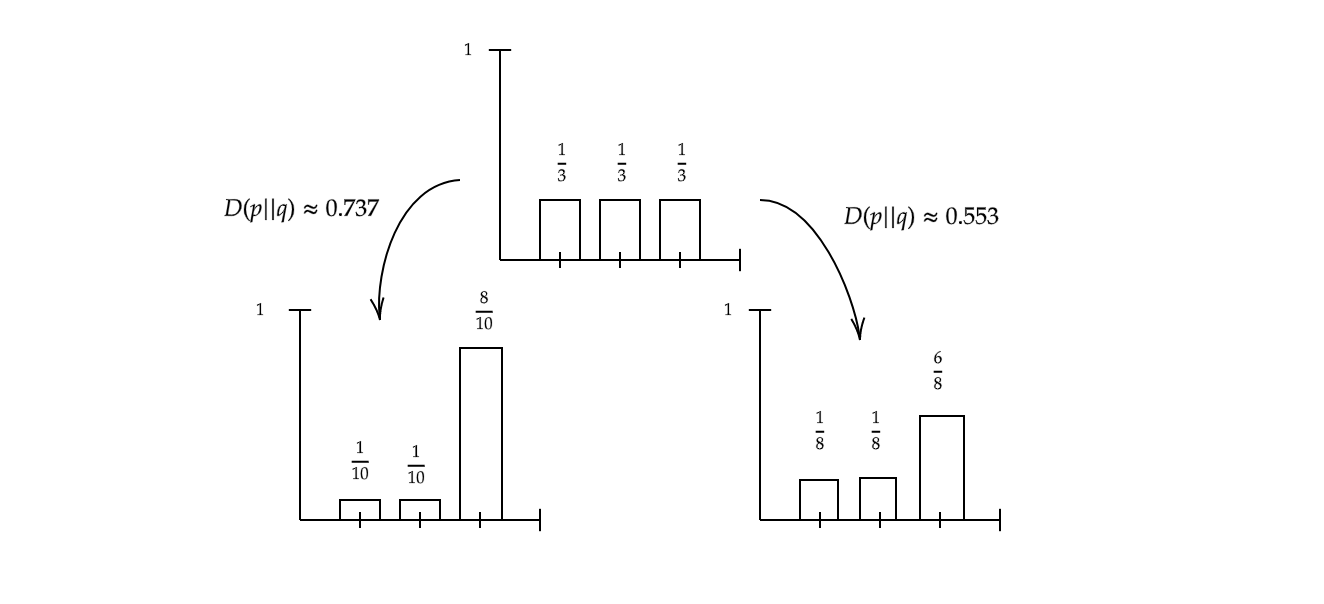

\[D(p || q) = \frac{1}{3} \log_2(\frac{8}{3}) + \frac{1}{3} \log_2(\frac{8}{3}) + \frac{1}{3} \log_2(\frac{8}{18}) \approx 0.553\]What this is actually measuring is how different the two distributions are. Let’s suppose we change q such that now $q(A)=q(B)=\frac{1}{10}$ and $q(C) = \frac{8}{10}$. Then $D(p||q) \approx 0.737$, which makes sense, since the distribution has become “more different” (see Figure 2).

Note that $D(p \vert \vert q) \neq D(q \vert \vert p)$, which means that the relative entropy operator is not a metric.

Also note that relative entropy is sometimes known as the Kullback-Liebler divergence.

A peculiar relationship

Now, we turn to ecology. Suppose we have a population $P$ of $n$ species which we represent as a vector $p(t) = (p_1(t),p_2(t),\ldots,p_n(t))$, where $p_i$ is the proportion of the population that is species $i$. Note that we have let these populations change in time. One can now define the well-known replicator equations for each proportion as:

\[\dot{p_i}(t) = (f_i(P) - \langle f_i(P) \rangle)p_i(t)\]Where $f_i(P)$ is the fitness of species $i$, which is a function of the other species in the population. We also have the mean fitness of species $i$, $\langle f_i(P) \rangle$. Note that if a species’ fitness is greater than the mean then it will grow in population. Thus, the fittest species will dominate all others.

Now this is where things get interesting. Remember the definition of relative entropy from before? Well we can actually use that for our vector of proportions since it’s a probability distribution (the probability you encounter each species). So let’s define another population $Q$, and its vector of proportions $q$, except we don’t let each proportion change with time. Let’s call this the resident population and let’s call population $P$ the invader population.

So let’s compute the relative entropy and take its derivative:

\[\frac{d}{dt}D(q||p(t)) = \frac{d}{dt} \left( \sum_i q_i \log \left( \frac{q_i}{p_i(t)}\right )\right ) = -\sum_i \frac{\dot{p_i}(t)}{p_i(t)} q_i\]If we substitute the replicator equation $\dot{p_i}(t) = (f_i(P) - \langle f_i(P) \rangle)p_i(t)$ and remember that $\sum_i q_i=1$, we get:

\[-\sum_i f_i(P)(p_i-q_i)\]We can refine this even further, as Baez and Pollard point out, there is an even nicer way to write this in terms of the original vectors:

\[\frac{d}{dt}D(q||p(t))=f(P)\cdot (p-q)\]So what is this equation telling us? Something quite extraordinary, actually. It’s telling us that mutual invasibility (a common criterion for a community’s stability), is actually an decrease in the difference of the invader and resident’s strategy (or distribution). Neat!

Until next time, I hope this post helped somebody learn something!

–Nasser

Sources

[1] Baez, John C., and Blake S. Pollard. “Relative entropy in biological systems.” Entropy 18.2 (2016): 46.

[2] Friedman, Daniel, and Barry Sinervo. Evolutionary games in natural, social, and virtual worlds. Oxford University Press, 2016.