Numerical integration using Gaussian quadrature

It’s been quite a while since I’ve seen Gaussian Quadrature, but it is an important result in numerical analysis with a very elegant proof incorporating many mathematical ideas. It can also be very useful, giving us a technique to numerically integrate polynomials exactly so long as they are of a certain degree (precision also will depend on your computer). Here I will explain the proof that gives Gaussian Quadrature its power, and we will see an application with some short Python code.

Theoretical underpinnings

First we need to introduce peculiar mathematical objects known as Legendre polynomials. Define the following inner product for two polynomials $P_n$ and $P_m$ of degrees $m$ and $n$:

\[(P_n,P_m) = \int_{-1}^{1} P_n(x)P_m(x) dx\]If we take ${1,x,x^2,…,x^n}$ as a basis for polynomials and apply Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization using this inner product (which I will not do here), we obtain the first n Legendre polynomials, which form an basis for polynomials on [-1,1]. It should be noted that the nth polynomial has degree n and will have n real roots.

I know that this definition seems a bit random right now, but trust me, this inner product will prove to be very useful!

Let’s introduce one more theoretical tool, known as a Lagrange polynomial (French people enjoy having similar-sounding names). It is often used to create a polynomial which interpolates some number of data points, which is easy to see from its definition: (One can learn more about their various uses here):

Definition: Suppose we are given k data points $(x_1,y_1,) \ldots (x_k,y_k)$ Define the Lagrange polynomial to be:

\[\mathcal{L}(x) = \sum_{j=0}^k y_j l_j(x)\]Where \(l_j(x) = \prod_{m \neq j}^{k} \frac{x-x_0}{x_j - x_0} \cdots \frac{x-x_k}{x_j - x_k}\)

The functions $l_j$ are often known as Lagrange basis polynomials.

This definition requires a bit of thought, but it shouldn’t be too hard to see how we chose $l_j$. Just notice that $l_j(x_i) = 1$ for $i=j$ and $l_j(x_i) = 0$ otherwise. This means that $L(x)$ interpolates the points exactly.

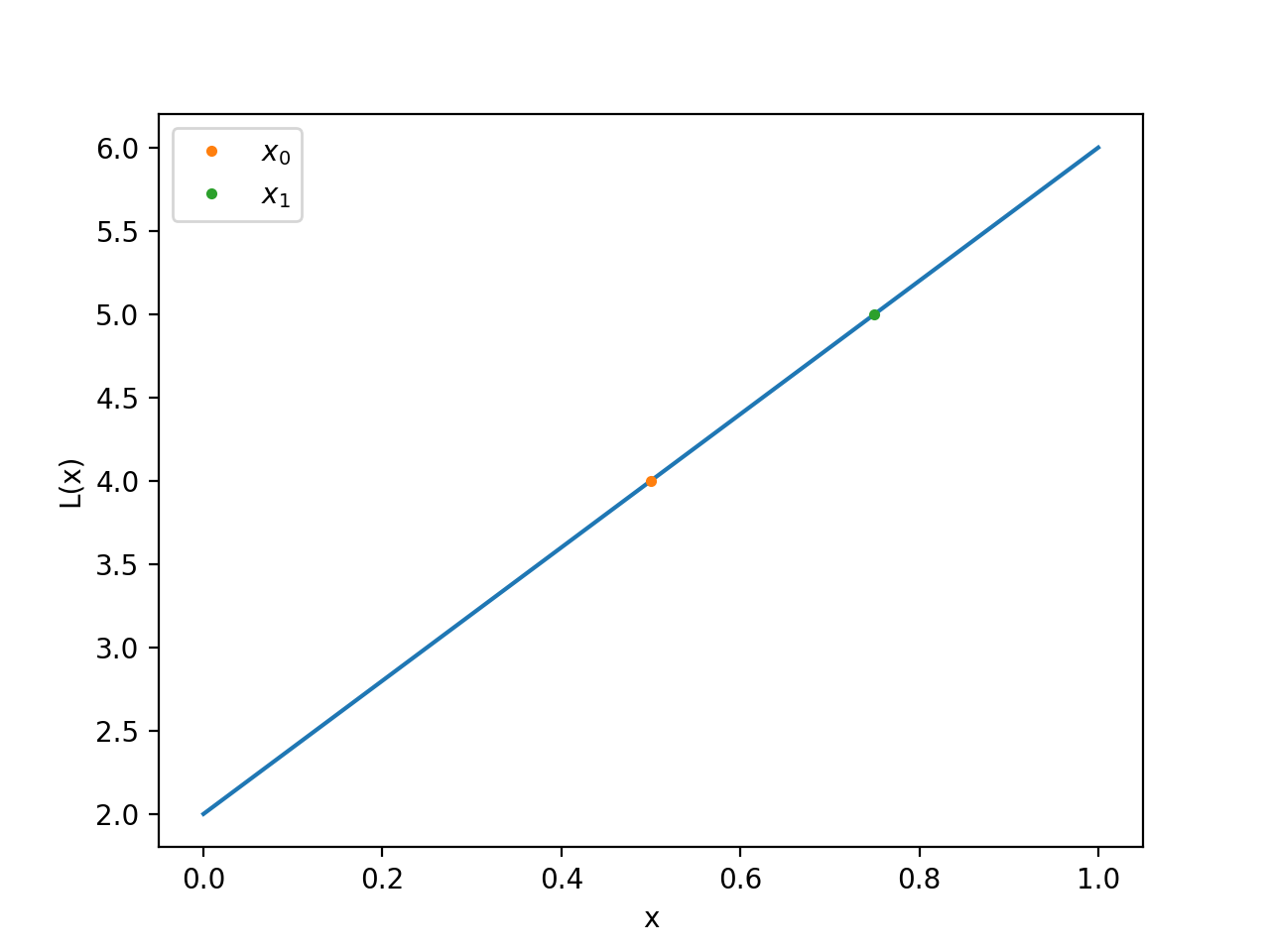

As an example, suppose we want an interpolating polynomial for the two points $(x_0,y_0),(x_1,y_1)=(1/2,4),(3/4,5)$. Then our Lagrange polynomial looks like:

\[L(x) = 4 \cdot \frac{x-3/4}{1/2-3/4} + 5 \cdot \frac{x-1/2}{3/4-1/2}\]Note that $L(x_0) = y_0 = 4$ and $L(x_1) = y_1 = 5$. Plotting this gives:

A linear function that indeed runs through the two points.

Now we remark a useful property of polynomials using the definition of the Legendre polynomial:

Remark: Suppose we have a polynomial $p(x)$ such that $deg(p) \leq n-1$. Then we can say that $p(x)$ satisfies an interpolation of $n$ points $(x_i,p(x_i))$ such that:

\[p(x) = \sum_{i=1}^n p(x_i) l_i(x_i)\]Where $l_i$ are the Lagrange basis polynomials. This comes from the fact that a Lagrange polynomial of degree $n-1$ interpolates $n$ points. Integrating yields:

\[\int_{-1}^{1} p(x) dx = \int_{-1}^{1} \left( \sum_{i=1}^n p(x_i) l_i(x_i) \right) dx = \sum_{i=1}^n \left( p(x_i) \int_{-1}^{1} l_i(x_i) dx \right)\]For future purposes, let’s define $w_i := \int_{-1}^{1} l_i(x_i) dx$.

Now for the main event! Here’s the proof that Gaussian quadrature works.

Theorem: Let x$_0$,x$_1$,…$x_n$ be the roots of the nth Legendre polynomial and $\mathcal{L}_i(x)$ be the $ith$ Lagrange polynomial. Let f be a polynomial of degree 2n - 1. Then the approximation,

\[\int_{-1}^{1} f(x) dx \approx \sum_{i=0}^{n} w_if(x_i)\]is exact.

Proof. We first rewrite f(x) in terms of our new orthogonal basis. Dividing by the nth Legendre polynomial we see that $f(x) = q(x)P_n(x) + r(x)$ where $ deg(q),deg(r) \leq n-1$ (by polynomial division), for some remainder polynomial r(x). Now, we integrate both sides of this equation to obtain:

\[\int_{-1}^{1} f(x) dx = \int_{-1}^{1} P_n(x)q(x)dx + \int_{-1}^{1}r(x)dx = \langle q(x), P_n(x) \rangle + \int_{-1}^{1}r(x)dx\]Now recall that on $[-1,1]$, the Legendre polynomials form a basis on the set of all polynomials. Thus, we can write $q(x) = c_0 P_0 + c_1 P_1 + \ldots + c_k P_k$, where $k \leq n-1$. Then $\langle q(x), P_n(x) \rangle = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} c_k \langle P_k, P_n \rangle$. But recall that Legendre polynomials form an orthogonal basis, so $\langle q(x), P_n(x) \rangle = 0$ (the choice of inner product should seem much less random now!). Now, we have:

\[\int_{-1}^{1} f(x) dx = \int_{-1}^{1}r(x)dx\]From the Remark above, since $deg (r) \leq n-1$:

\[\int_{-1}^{1} r(x) dx = \sum_{i=1}^n r(x_i) w_i(x_i)\]Now we notice that: \(r(x) = \sum_{i=0}^{n} w_i\mathcal{L}(x_i)\)

Only if r is a polynomial of degree \(\leq n-1\). Now, we use our assumption that the interpolating points $x_i$ are the roots of $nth$ Legendre polynomial. Then we have $f(x_i) = q(x_i)P_n(x_i) + r(x_i) = q(x_i) \cdot 0 + r(x_i) = r(x_i)$. Thus we can effectively “convert” our integral into a discrete sum:

\[\int_{-1}^{1} f(x) dx = \int_{-1}^{1}r(x)dx = \sum_{i=1}^n r(x_i) w_i(x_i) = \sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i) w_i(x_i)\]An Example

We will now apply Gaussian quadrature for $n=3$, which allows us to integrate polynomials of degree less than $2n-1=5$. The value for the third Legendre polynomial is $f(x) = x^3 - \frac{3}{5}x$ (from Wikipedia, although it could be easily computed using Graham-Schmidt orthogonalization).

Here’s our schema:

-

Find the roots of the third Legendre polynomial.

-

Create a system of three equations in terms of the three weights $w_i$.

-

Solve the linear system to find the weights and compute the sum.

The roots of the Legendre polynomials are $x_1 = -\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}},x_2=0,x_3 = \sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}$. Since we’re in the case of $n=3$, we must find the weights $w_1,w_2,w_3$. An easy way to do this is to set up a linear system. Since the weights will be the same for integrating any polynomial of degree $\leq 5$, we can let $f(x) = 1,x,x^2 and apply Gaussian quadrature to solve for the weights:

\[\int_{-1}^{1} 1 dx = w_1 f(x_1) + w_2 f(x_2) + w_3 f(x_3) = w_1 + w_2 + w_3 = 2\] \[\int_{-1}^{1} x dx = w_1(-\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}) + w_3(\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}) = 0\] \[\int_{-1}^{1} x^2 dx = w_1(\frac{3}{5}) + w_3(\frac{3}{5}) = 2/3\]Now, let’s solve the linear system numerically and write some code that computes a polynomial.

We import the library numpy and the linalg sub-package from the scipy library; the latter of which is very useful for solving linear systems.

import numpy as np

from scipy import linalg

First we solve the linear system and save the weights as solutions:

#A is a matrix containing the linear system

A = np.array([[1,1,1],[-np.sqrt(3/5),0,np.sqrt(3/5)],[3/5,0,3/5]])

b = np.array([[2],[0],[2/3]])

weights = linalg.solve(A,b)

#Let's create an array containing the points x_i

roots = np.array([-np.sqrt(3/5),0,np.sqrt(3/5)])

Now let’s define a function which applies Gaussian quadrature $n$:

#the function which applies the rule

def integrate(n,function,weights,roots):

integral = 0

for i in range(n):

integral += weights[i] * function(roots[i])

print(integral)

Now we can do a specific example integrating $x^4 + 42x^3$:

#the function to integrate

def f(x):

return pow(x,4)+42*pow(x,3)

integrate(3,f,weights,roots)

Output: 0.4

Which is the correct answer.

The below code chunk uses exactly the same function to integrate the polynomial $x^{6} + x^{5}$, but since it’s degree is greater than 5, we get a bad approximation:

#our new function

def g(x):

return pow(x,6)+pow(x,5)

integrate(3,g,weights,roots)

Output: 0.24

Which differs from the correct answer of $\frac{2}{7}$.

Anyways, I hope this post helped someone to understand Gaussian Quadrature! Note that there are many other quadrature rules to numerically integrate polynomials and other functions, such as Newton-Cotes Quadrature, Gauss-Jacobi Quadrature and more. I simply find Gaussian quadrature to have a particularly interesting proof.

Until next time!

–Nasser